Meet Our Alumni: Zeina Mohammed

“People Need English Majors”: Sitting Down with GW English Alumna Zeina Mohammed

as told to Maryam Gilanshah, Creative Writing 2021

Why did you choose GW and Washington, D.C.? Why make that switch?

Z: So my family actually lives in Washington DC. We’ve bounced between Washington and different locations all my life because my dad is based here. So when I made the decision to go to St. Andrews, they were still living abroad. And I really liked St. Andrews, and I went in not really knowing what I wanted to do. And it was my first time living in a small town, and it was really cute for about three seconds. And then I was like: “okay, time to go back to the city.” And so they didn’t have a journalism program. But during the second half of my first year, I realized that I, I’ve always been interested in English. And so that’s what I did. At St. Andrews, I realized that I’d also like to tack on media journalism, if I could. So I wanted to go to a school that was a little bit more modern. St. Andrews is a very kind of like, older, traditional institution, which is really great for literature, if you want to study Chaucer, but not so much if you want to study anybody, not white from, you know, 20th century onward. So I picked GW because I had always lived in the DC suburbs. And so I’m very fond of the DMV area. But also, because both in my English work, and in my journalism work, I have a big international focus. And I was hoping that since GW is so well-known for international relations, and kind of like looking at that, you know, that would leak into other majors that aren’t an Elliot. And I did find that to be true.

That’s so interesting, I didn’t really think about how I kind of like finds its way into the other majors and how it’s kind of ubiquitous, insidious, and that kind of way.

Yeah. And I think even in extracurriculars, like, I wasn’t necessarily looking to study international affairs, but just by virtue of the fact that so many of your friends are and a lot of the events and you know, clubs, kind of have that leaning, like you do learn so much. And I think university is the time when, like you will observe everybody else’s perspectives. So I wanted to make sure that there were diverse perspectives.

Do you think that diversity kind of manifests itself in the student body?

I do think that like, just by virtue of the fact that the students are diverse, the curriculum does kind of have to tailor to that. Because if I come from somewhere, and my friend comes from somewhere else, and that friend comes from somewhere else, we’re all looking to see how this applies to our particular culture. I think with homogenous societies, like we, for example, if I went to school, and we all grown up in the same town, there are things that we’d accept as the norm without necessarily challenging that. So I think like a place like GW will really have you understanding that almost nothing is objective. Like there’s different ways to see everything, even things that you think are so mundane and like, set in stone.

That’s important in English, too, because it is so subjective. Like there’s no like science to it.

That’s especially important because I think majors like English, like history, have traditionally had such strict gatekeepers. And so in a lot of universities, they tend to move a lot slower than majors like media or engineering that have to be very fast paced and keep up because they’re linked to real world industries. So you can literally have English department [where] their curriculum hasn’t changed since the 1600s. It was really nice to see that the GW faculty is kind of committed to diversity and inclusion, but also to like modernizing and adapting to what their students want.

Did you see that in any particular way in your English classes? Or did you feel like it was more in the journalism classes because they have to keep up, they’re more about like production than English, which can, as you were saying, rely more on the history of it?

Yeah, I think, um, I was so journalism was my minor and I didn’t really commit to it until junior year. So like, English was the majority of like what I did, and I was really pleasantly surprised to see that there the faculty was more diverse than I was expecting, coming from a school where it was all white men. And it was really cool to see that even if they were teaching traditional books, it would be with the new and modern lenses that were focused on. Either like race or gender or sexuality. And so even if we’re reading a text that people have been reading for hundreds of years, we’re reading it within the context of what’s happening today. And also the department head was so receptive to changes in curriculum when they felt a little old.

And I was paired with Kavita Daiya, who taught postcolonial studies and I think she’s one of the most brilliant scholars that I’ve ever met. And her work is so interesting, and so different than anything anyone’s doing. And then I had Tony Lopez overseeing the honors department and he was doing a lot of stuff with Chicano literature and the 21st century. I just thought it was so fascinating that professor to professor, everybody had such a different focus. It gave you such a wide variety of things to choose from when it came to studying. And then Professor Chu, I think that was one of my first professors. When I took Children’s Lit with her, you’re like, wow, everything I’ve read in childhood is so problematic. Throw it away. Everyone, everything is bad for you. But like in the best way possible, like I think, I think people are too forgiving to historical literature. Because it is always like, you have to, you have to consider the times; but at the same time, that was also like painfully misogynistic, and like a remnant of colonial history, or whatever. And Children’s Lit was such an interesting class, because we read things like The Lion, The Witch and The Wardrobe. And there are just so many things that you miss when you’re a child.

I was always interested in literature because I’m very interested in how narrative shapes bias, and shapes identity and stereotyping. I think growing up, it was so easy for me to see how the work that I was consuming, shaped my, how I view the world. I went to middle school here for a little bit, say, fourth to sixth grade, and then I moved to Kuwait to finish seventh and eighth grade. And when I was in Kuwait, I was still an American school. So it was still largely an American curriculum. But what we read was a little bit more tailored to that region. And I think it was the first time that I was able to exist outside of kind of the American lens. And it was interesting for me to see how much that changed the way that I saw other people, the way I conceptualize things.

And then it was easy to see, based on what like, my white peers were reading outside of school, their inability to understand me and where I came from, because I’m from Sudan. So I think my goal was to work in publishing to make sure that like more diverse books were published, because I think it’s important not just for people to see themselves identified, which is really important, especially when you’re a child, but also because we become what we read, and what we consume. And if that’s not reflective of the world done, we’re not able to engage with it in like an honest and accurate way.

So I know that you did your thesis on Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Half of a Yellow Sun. Was that at all inspired by the experiences you were just talking about? How examining how media, especially literature influences you in that kind of way?

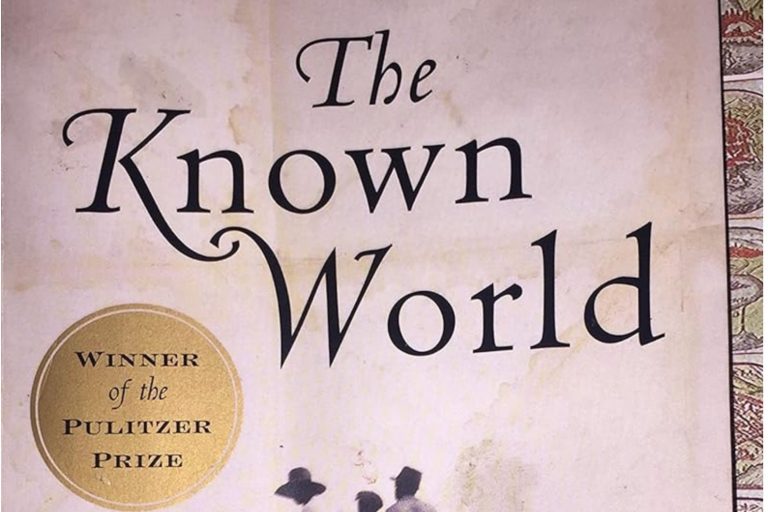

So I’d read Half of a Yellow Sun in high school, and I enjoyed it, but I don’t think I was quite there yet. To be able to fully understand it. And so in my first semester, I took Black Woman Writers with Professor Jennifer James, and we read that book again. And I just thought it was such an important piece of work. Because it highlighted the kind of things I was talking about but in such an artistic way.

I am interested in like societal hierarchies, and how that dictates who gets to speak, who gets ownership and authorship over history, and then how that kind of trickles down into society. So I chose that particular topic because I think we do a good job of looking at intersectionality as it exists in the domestic space. But I wasn’t always satisfied with the conversations that we had about things like post-colonialism, how intersectionality plays out.

Something that I really wanted to speak to is how, in particular in Anglophone African countries that had settler communities how does race play out differently than it does in a US context. How is class play out differently in a US context? And then what does that mean for wartime coverage? Because I always found myself really annoyed about the scholarly research that was available, not just for Sudan, but for non-Western spaces in general. And that’s because I think diversity isn’t just looking at other countries, it’s looking at other countries through the perspective of the people who really live those experiences. And unfortunately, the authorship generally does not go to them for reasons of race and class.

Biafra [and] Rwanda, those are the two I think, like, African conflicts that the West loves to continuously speak on without a right and without a full understanding of what happened. And so I just wanted to look at the reasons why that was, and that text very beautifully offered me an avenue to do that.

Was the thesis part literary analysis, part like scholarly research, bringing in related scholarship on the topic?

So I picked two characters that I thought represented the two different things I was trying to speak on. And then I looked at the ways that she utilized literary devices to illustrate the oppression that was happening in real world in real time. So it was more literary analysis than it was like, like a historical analysis on the conflict itself; I engaged mostly with the literature itself, and the devices that she used to convey the issues that she was saying, than, you know, the historical media coverage of the Nigerian conflict.

I know you’re at American University studying journalism for your Master’s. What was that decision going from journalism as a minor? How did you decide to pivot and more focus on journalism?

Coming into uni, I, my goal was to work in publishing, because, I’d always wanted to diversify narratives about certain parts of the world. So I thought that publishing would be a good avenue to do that. And then the more that I engaged with both English and journalism at GW, I found that media is probably a better fit for me and what I want to do, especially considering the fact that I’m very concerned with international coverage. So as I started to take my minor classes, and I picked up journalism as a minor because I wanted to become a stronger writer. Because I think usually when you’re writing in an article for an English class, you’re trying to make it as long as possible. And then you go to journalism and you have 15 words. But I wanted to be able to do both. And I found that I really, really did enjoy journalism writing.

So when I graduated, my goal was to find work in media. And there were a lot of fellowships and internships that I was looking at that unfortunately got canceled because of the pandemic. And so I decided very last minute in June to apply to the AU program that started in August. I was desperate for work experience in the fields. And so you know, AU has a really, really brilliant program. And luckily, journalism masters tend to be a year only, because I wasn’t trying to spend too much time in school. I think I was just looking for something to tide me over and build my resume while the world was on a COVID standstill. I always love being in school, but I was looking for something that was practical and so luckily there’s not too much theory in journalism even now. I think the course feels more like a training program. I go in and my professors are like, so we’re gonna pretend we’re in a newsroom, just go out and do it.

But what really drew me to AU is the fact that they have three different tracks for their programs. There’s broadcast, investigative, and international. I was always interested in doing investigative work. But again, the fact that they just had an international program just signaled to me that it would probably be a good place that would allow me to be more globally minded. And like, I think that that has been true.

Do you see any huge differences between GW and AU in journalism or with your classmates, since you talked about GW’s more international base?

So I think both schools are understandably, politically leaning. So SMPA and AU, both are great places for people who want to cover the White House or want to cover domestic politics. It’s hard for me to compare the two because I wasn’t a full major SMPA. And also now I’m a graduate student. So things are a little bit more specific, but I do feel like AU’s program allows you to specialize a lot more.

Do you have any professional or personal heroes that inspired either you studying English or GW and picking the particular classes you did? Or in deciding to go to graduate school or study investigative and more international leaning journalism?

Yeah, so I think there are actually two people that I can pinpoint. And I’ve actually gotten to meet and get to know them both personally during my time as an undergrad. One of the first pieces of literature that I ever read that I felt lik, accurately spoke to my experience as a person, was the work of a Sudanese American poet called Safia Elhillo who released a book of poetry called The January Children and even before that was doing stand-up. I’d never necessarily engaged with any literature that was specific to my particular diaspora group, on top of the fact that I think she’s one of the most brilliant writers that I’ve ever read. Seeing how much that had an impact on me really solidified the importance of representation and literature. And so I almost wrote my thesis on her, and kind of wish I had. I was able to actually meet her by my sophomore junior year at GW, and like, we’re, like, casual fans now. She’s like, absolutely brilliant. She’s continuing to write absolutely wonderful things. So I think like, she was a very big inspiration for me and choosing to pursue English, because I was able to see how much her work really helped validate my experiences in a lot of ways.

And then on a on a professional level, there are two, again, Sudani, there are two sisters. Nima Elbagir is the older one. And I grew up seeing her. She was a CNN reporter when I was growing up – still is – and she was the only person that I saw on TV that looked like me. I didn’t know she was Sudanese for the longest time, and then when I found out it was even more like special for me. And so she’s done, absolutely amazing reporting and is responsible for a lot of the really powerful and more accurate coverage that my country’s gotten on the international stage. So I think she’s an absolute giant, and her younger sister is a pretty prominent journalist. Now, I think two or three years ago, in my junior year, there was a revolution in my country, and she almost single handedly covered it. And I just thought it was so amazing that like one well placed, culturally specific person can dictate whether or not the most important event in the country’s history gets covered or not, because if she hadn’t been there, like, I don’t know that we would have necessarily had news coming out of the country. And especially towards the beginning, there wasn’t a lot of international interest.

And so I got to meet her as well in December 2019 the last time I went back home. And she gave me a lot of career advice that has that I’ve kind of used as a guiding compass, when it came to like going to graduate school and picking my courses. Even now, like applying to jobs, and things like that. And I think that also, again, speaks to like representation, where, like, if I hadn’t necessarily seen these two people doing these things, I might not have even thought that to do them. Because I’m like, growing up, I’m like, somebody needs to do a better job at this or that, but I wouldn’t have necessarily thought that I would be that person if I hadn’t seen somebody that you know, look like me or came from the same place as me doing it and doing it honestly, better than anyone in my opinion, in my unbiased opinion. I think especially meeting Yousra, the [other] journalist, is what really committed me to the field. Because I think I just need to see somebody who shared the same goals as me do it and do it with the confidence. And so I’m like, “Okay, well, if you say so then I’m done.” And there are already 30 people who also that came before me who are already paving a bit of leeway for me to be able to exist and do the work that I want to do without having to sell out once I got to middle management. Because I mean, journalism, the gatekeepers of the industry have a certain bias that you know, is harmful to a lot of communities that are not dominant. So I think seeing her be able to produce the kind of news coverage that does break a lot of stereotypes and be able to be applauded by so many dominant news agencies and published in so many dominant news agencies gives me actual hope that that bias doesn’t need to be present in my work for me to work at news giants.

Are there media sources that you turn to that you’re particularly fond of? Whether it be an actual news source, a book, a writer or a TV show —something you turn to and you’re like, this is an example of what I want things to be?

In terms of new organizations, I’m really fond of al Jazeera. I think particularly when it comes to East Africa, al Jazeera, more than other news organization, tends to have more accurate coverage. And I think it’s because they’re one of the only bigger news organizations that’s not based and owned by a Western country. And so I think a lot of the Islamophobic tendencies that tend to seep into news coverage aren’t present, because they’re a state owned organization in a Muslim-majority country. And that’s not to say that they’re perfect, but at least when it comes to their reporting about Sudan, they have more robust reporting, I guess, because we’re geographically closer, so we’re actually an interest region for them. And there are a lot of Sudani reporters present at Al Jazeera, which I think for me just proves that like, you need to have people from different countries in your newsroom because there’s no other way that you will accurately be able to cover and evenly cover things that are happening all across the world that goes to many countries.

There’s a podcast called Media Tribe, by a reporter named Shaunagh Connaire . She’s an Irish reporter from Channel Four news, I believe. And every episode, she will interview a journalist or a storyteller, and get them to speak about their craft and their experiences. And her goal is to kind of illustrate how important media and storytellers are, especially in this age of increased distrust of media and storytelling. And so I think it’s, it’s an interesting podcast for me, because even career-wise, like, there’s a lot that I’m learning and they give a lot of advice, but it’s also so cool for me to see the breadth of things that people can do. Like media doesn’t just in need to be writing an article. There’s so many ways to present both the news and stories in general, whether it’s fiction or nonfiction. There’s so much more that you can do if you’re a storyteller. And it can involve STEM…we can do STEM things to like be storytellers. So it’s really, really cool. I think it’s helping me realize that I don’t necessarily have to stay in such a tight box. If I want to tell stories, I can do that in so many different avenues. And people come in from so many different backgrounds as well and tell sorts of stories, for all sorts of reasons. And so I think it’s absolutely fascinating podcast for anyone who wants to go on later and tell stories.

The rise of podcasts is like a really good example of people diversifying the way in which they communicate material, especially if you’re trying to humanize a story. It’s so crucial now to adapt to like the technology age, because you keep hearing that journalism is dying. It’s not dying, traditional journalism is. Or it might not exist in the way that it’s traditionally looked. It’s just adapting as it needs to the changing world. But I think like now, more than ever, it’s important for us to broaden idea of what a storyteller is, and how they how they do their job.

Do you have anything that you want to plug?

All of the stuff that I’m working on doesn’t come out until the summer, so Google Alerts, guys.

I think one thing that I didn’t necessarily not take seriously, but local news was never necessarily something that I’d consumed. And it was never something that I thought to do either. I think anything journalism, you think like CNN, BBC, like war, coverage, all of this stuff. But last semester, as part of our program, graduate students publish articles on the Wash. And we’re tasked with picking a particular neighborhood in DC, so I covered the Shaw-U Street area and Silver Spring, and then having to build sources in that community and cover what’s happening. I think it was probably the most important class, I feel like I’ve taken to date, because a lot of times we’re looking at what’s happening in like, Malaysia, or in Namibia, or in Argentina. But the most important thing to us is what’s happening in our own backyard and I think a lot of times that gets overlooked and so that was a really cool classroom to begin to learn to value and to cover my community and not just like what’s happening halfway across the world. I think to date that’s the project that I’ve been the most proud of. I think I wrote eight articles covering that area and then covering DC at large when the elections happen so I was like, such a cool time to be a baby journalist. Because you know, COVID was happening the election happened insurrection happened and like to be in DC and to have my eye on what’s going on. Like that was the most valuable learning experience ever.

I think it was an issue at first because I felt so much internal pressure to find a niche. But my professor said don’t pigeonhole yourself because you’ll largely be pigeonholed into doing something in the actual industry. I think I was so focused on what I like to do that I didn’t realize that naturally, as you move, you find out what you don’t like to do. And over time you’ll find yourself covering this niche that you actually like…it’s important to have a focus, to not be directionless, but at the same time, don’t limit yourself. That even extends to…English. If you study English, you don’t necessarily have to be an author. Take the classes you think are interesting. We’re not groomed for a particular job. English is more about understanding and analyzing information. And that’s valuable for anything. People always need English majors.