Digging

Between my finger and my thumb

The squat pen rests; snug as a gun.

Under my window, a clean rasping sound

When the spade sinks into gravelly ground:

My father, digging. I look down

Till his straining rump among the flowerbeds

Bends low, comes up twenty years away

Stooping in rhythm through potato drills

Where he was digging.

The coarse boot nestled on the lug, the shaft

Against the inside knee was levered firmly.

He rooted out tall tops, buried the bright edge deep

To scatter new potatoes that we picked,

Loving their cool hardness in our hands.

By God, the old man could handle a spade.

Just like his old man.

My grandfather cut more turf in a day

Than any other man on Toner’s bog.

Once I carried him milk in a bottle

Corked sloppily with paper. He straightened up

To drink it, then fell to right away

Nicking and slicing neatly, heaving sods

Over his shoulder, going down and down

For the good turf. Digging.

The cold smell of potato mould, the squelch and slap

Of soggy peat, the curt cuts of an edge

Through living roots awaken in my head.

But I’ve no spade to follow men like them.

Between my finger and my thumb

The squat pen rests.

I’ll dig with it.

(Photo by Alex Cohen)

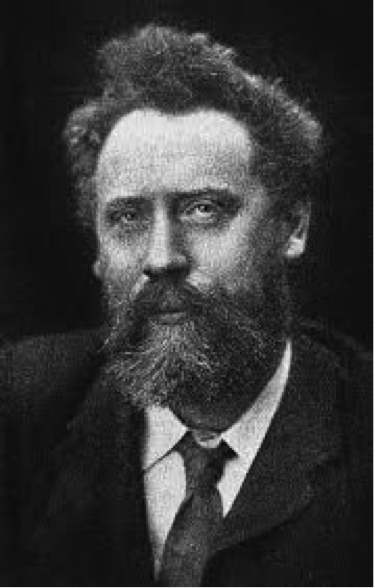

I read “Digging” for the first time last semester and was very moved by the power of Heaney’s imagery. As a young person forging my own path—like the speaker of “Digging,” also with a pen because, yes, I’m an English major—the poet’s words resonated with me in a very real way.

When asked in an interview about “Digging,” Heaney explained that “the poem I began with as a writer, ‘Digging,’ was truer to my phonetic grunting from south Derry than to any kind of iambic correctness from the books.” The word “digging” first appears in relation to the physical act of digging that the speaker describes when speaking about the men in his family, but “Digging” is about much more than the literal process of digging. The speaker digs for memories and for a new path. “Digging” illustrates the push and pull of Heaney’s allegiance to his hardworking forefathers, or his Irish roots, while also exploring his choice of forging a new path with his pen. While many scholars suggest that “Digging” is about Heaney’s commitment and commemoration of his father and grandfather’s labor, I propose that “Digging” is less veneration for his ancestor’s work and more a lamentation of the speaker’s unfitness for the path give to him by lineage.

“Under my window, a clean rasping sound / When the spade sinks into gravelly ground: / My father, digging. I look down.” Here, the image of the speaker is elevated and looking downward, which indicates the figurative sense of looking down on the act of digging. Heaney reinforces the likelihood that the speaker takes a dim view of digging, for the “rasping sound” he hears from under his window has a rough, harsh, and mostly unpleasant connotation. The alliteration of the “g” in “gravelly ground” is softer and grounding, but the word “gravelly” is synonymous with “rough,” “gruff,” and “harsh.” As the poem continues, the two conflicting and opposite possibilities of the speaker’s either esteem or disdain for his father and grandfather’s digging becomes increasingly muddled. This first scene serves to set the tone of Heaney’s ambivalence as he continues to relive and question the past’s effect on his future.

At the beginning of “Digging” the speaker was unsure that he could stick to his literary guns—pun intended—when faced with the “living roots” of his forefathers’ history, but at the end the speaker seems to reach a reconciliation. That reconciliation is the fact that no one would ever say of him what he said of his father and grandfather in lines 15-16 ““By god, the old man could handle a spade / Just like his old man,” and that instead, he would try to handle his pen as well as they handled their plows.

—Alex Cohen

Alex Cohen is a sophomore majoring in English.