Introducing Jenny McKean Moore Writer-in-Residence Melinda Moustakis

|

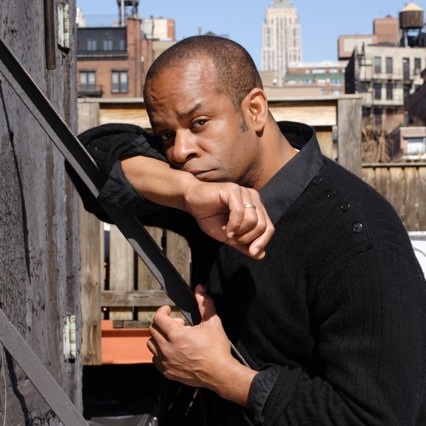

| Jenny McKean Moore Writer-in-Residence Melinda Moustakis |

The Jenny McKean Moore Fund was established in honor of the late Jenny Moore, who was a playwrighting student at GW and who left in trust a fund that has, for more than 40 years, encouraged the teaching and study of Creative Writing in the English Department, allowing us to bring a poet, novelist, playwright, or creative non-fiction writer to campus each year. While in residence, the writer brings a unique experience to the GW community, teaching a free community workshop for adults along with Creative Writing classes for GW students.

This year we are pleased to welcome Melinda Moustakis, our 41st Writer-in-Residence. Professor Moustakis is the author of Bear Down Bear North: Alaska Stories, which won the Flannery O’Connor Award for Short Fiction and the Maurice Prize. She was a 5 Under 35 selection by the National Book Foundation; you can watch a Vimeo interview about that award here. Professor Moustakis received her MA from the University of California at Davis and her PhD from Western Michigan University. Her story “They Find the Drowned” won a 2013 O’Henry Prize and her work has appeared in Alaska Quarterly Review, Kenyon Review, New England Review, and American Short Fiction. We caught up with Professor Moustakis as she settled into campus to ask her a few questions. Join us on September 23, when she kicks off our Jenny McKean Moore Reading Series for the semester.

What attracted you to the position at GW, and as Jenny McKean Moore Writer-in-Washington?

Tell us a bit about your debut story collection, Bear Down Bear North: Alaska Stories. The linked stories are all in some way connected to a family of homesteaders in Alaska – can you describe this setting for us? What sets this location apart from other settings in contemporary U.S. literature?

My focus is mostly south-central Alaska– the Kenai Peninsula and Anchorage and surrounding areas. The book covers three generations of one family because I was thinking about my grandparents, who homesteaded in the fifties, and my parents who both grew up in Alaska, and then my relationship to their ties to this landscape as well as my own. The characters in my book hunt and fish and tell stories, ones best told around a campfire or at the bar. But more importantly, I wanted to reveal the stories that these characters try to keep hidden, perhaps even from themselves. There’s so much mystique surrounding Alaska and often people in the lower 48 imagine this beautiful and majestic place they want to visit before they die and they call it the last frontier. But my goal is to write beyond the beauty and to reveal the complexities, the ugliness, the knife-edgeness of this place and its inhabitants. I like to call my writing Northern Gothic. Alaska, like Hawaii, is a state literally set apart from the rest of the U.S. The sheer scale of the wilderness and the harshness of living are added elements to any story I write. A couple could be having a disagreement, which happens anywhere, but at any moment a moose could walk into their yard. I’ll never tire of making a moose-in-the-yard moment an important part of a story.

My focus is mostly south-central Alaska– the Kenai Peninsula and Anchorage and surrounding areas. The book covers three generations of one family because I was thinking about my grandparents, who homesteaded in the fifties, and my parents who both grew up in Alaska, and then my relationship to their ties to this landscape as well as my own. The characters in my book hunt and fish and tell stories, ones best told around a campfire or at the bar. But more importantly, I wanted to reveal the stories that these characters try to keep hidden, perhaps even from themselves. There’s so much mystique surrounding Alaska and often people in the lower 48 imagine this beautiful and majestic place they want to visit before they die and they call it the last frontier. But my goal is to write beyond the beauty and to reveal the complexities, the ugliness, the knife-edgeness of this place and its inhabitants. I like to call my writing Northern Gothic. Alaska, like Hawaii, is a state literally set apart from the rest of the U.S. The sheer scale of the wilderness and the harshness of living are added elements to any story I write. A couple could be having a disagreement, which happens anywhere, but at any moment a moose could walk into their yard. I’ll never tire of making a moose-in-the-yard moment an important part of a story. Tell us what you’ve been working on. Will you be presenting from Bear Down Bear North as well as some of your new work when you open the JMM reading series in a few weeks?

Who are some of the short story writers you have been reading lately?