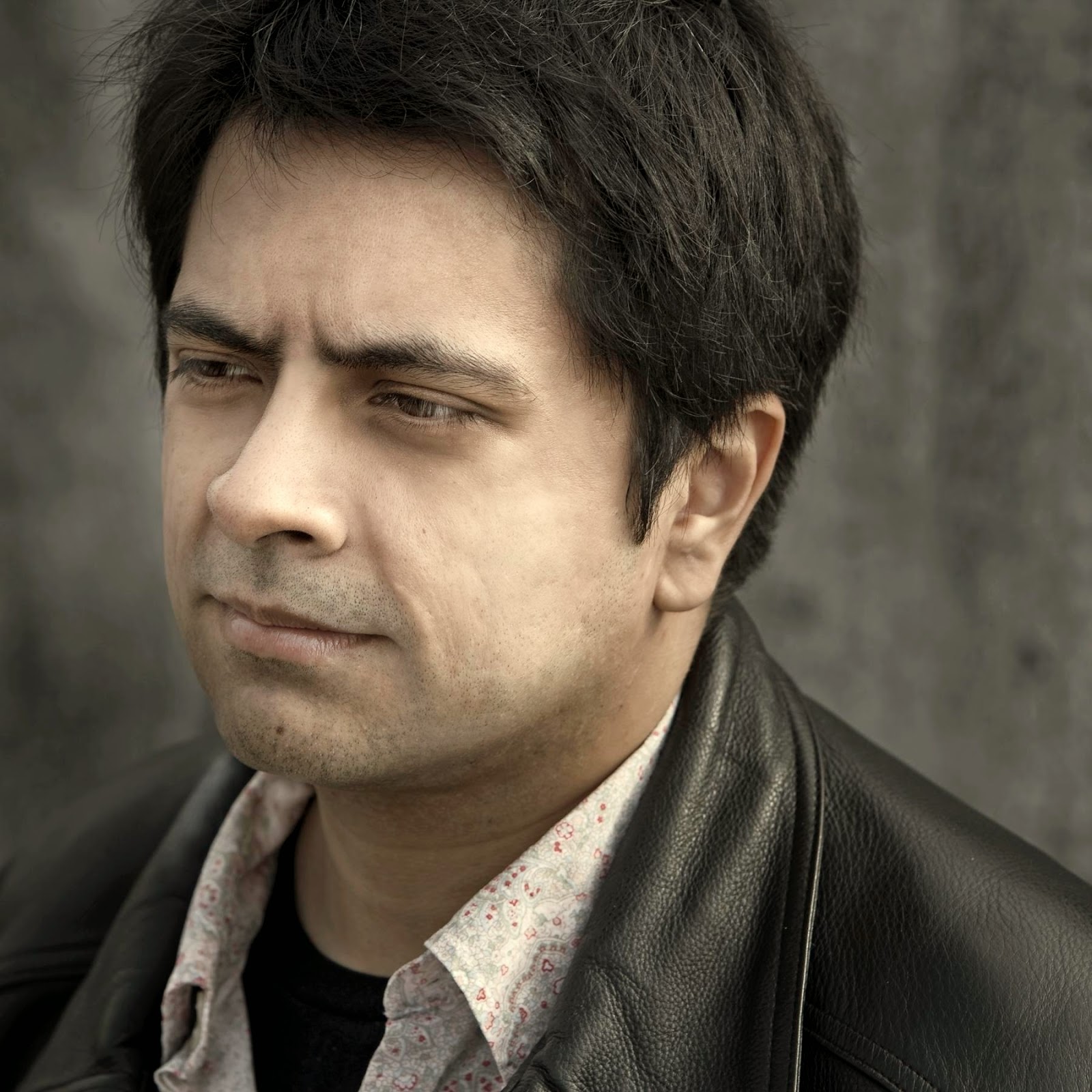

This year we are especially proud to host Brando Skyhorse, who won both the 2011 PEN/Hemingway Award and the 2011 Sue Kaufman Prize for First Fiction for his novel The Madonnas of Echo Park. This year, Professor Skyhorse has published, to great acclaim, Take This Man: A Memoir, which tells the story of his “American Indian” heritage and childhood — a heritage that was in fact based on stories that his mother invented; Professor Skyhorse learned years later that in actuality he was not in fact the son of an American Indian activist but of a Mexican man who had left the family when his son was just three years old. Professor Skyhorse has been talking about and reading from Take This Man over the course of Summer 2014; the GW community will have a chance to hear him read from this work when he opens the Jenny McKean Moore reading series on September 11. We sent Professor Skyhorse some questions in anticipation of his arrival.

What attracted you to the position at GW, and as Jenny McKean Moore Writer-in-Washington?

For years my mother toiled away at a memoir called “The Beginning” that, sadly, never found an end. It was a privilege to edit some of her pages into a short excerpt that I included in my latest book but I wondered how much more she could have accomplished if she’d had taken writing courses. Knowing the JMM fellowship lets its recipients teach a free community based writing workshop made this position irresistible. What an incredible opportunity for both visiting writer and students alike! I hear new voices that I might not easily find on a college campus and they get writing experience without paying for an MFA course. This workshop could be the difference between a stack of pages that stays in someone’s drawer and a novel that goes on to be published and changes the lives of its readers and its author.

This applies just as much to college students eager to know more about the writing process. I decided to become a writer when I was in college which I owe to some incredible teachers. They helped me understand that writing is something that’s impossible to do well without constructive feedback and empathetic encouragement. Many writers aren’t taught how to deal with creative frustration and rejection. It will be my privilege this year – and it is indeed a privilege – to encourage writers both on and off campus to turn their creative baby steps into confident strides.

You arrive as this year’s Jenny McKean Moore Writer-in-Washington having just published Take This Man: A Memoir. It traces the life of “Brando Skyhorse,” the American Indian son of an incarcerated political activist. As it turns out, however, this life, your life, was based on a fabrication. Tell us a bit about what motivated this fabrication and how you felt when you learned about it.

My mother was a fantastical storyteller. I can only imagine how much more my students in DC would learn this year if she was their teacher instead! When I was three my Mexican father abandoned me so my Mexican mother reinvented us both as American Indians. She did this in part because she found a pen pal – slash – potential husband in prison who was willing to be my surrogate father and thought it’d be easier if I believed this man was my biological father. She also did this because she was greedy for a specific part of life that all of us take for granted via Facebook and Twitter: reinvention. We share just the parts of our life online that we want people to know about and can get instant affirmation about this fictional representation of ourselves. That affirmation is incredibly important to some people. It would have been important to my mother.

When I was twelve or thirteen I discovered I was Mexican and continued the lie because I ran the risk of emotional and/or physical abuse if I contradicted my mother. There wasn’t much danger of that at first because my “Indian” upbringing was all I knew. Over time, my mother and I clashed over who and what I told people because I’d felt she’d forced me to live a life that was one massive lie. It took years more of processing and, in particular, writing, to come to an understanding of not only the life I lived but who I really am: a Mexican-American author with an American Indian name. Pretty exclusive club, that!

What are a few of the things you hoped to accomplish translating your story into creative non-fiction? What are some of the challenges of moving between fiction and creative non-fiction?

When I tried writing fictionalized elements of my life it never worked because the events, ironically, seemed too unbelievable. In fiction, characters need motivations and you need to demonstrate the specific actions that shaped them into who they are. In non-fiction, if you record a person’s actions, sometimes it’s enough to say, “Well, she was just crazy.” This memoir might have been easier to write as a novel but I wanted this book to reach other survivors of dysfunctional families with a seal of approval that said, “This really happened and I survived. Maybe I’m not perfect but I’m here. You can survive, too.” That non-fiction seal should mean something. It should tell the reader that the writer lived through every painful event on the page and found the courage to share that pain so that you could learn something from it. That’s why it’s important to have two separate categories and that we respect what makes fiction different from non-fiction.

Tell us what you’ve been working on. Will you be presenting both from Take This Man and some of you new work when you open the JMM reading series in September?

I’ve been promoting Take This Man for the past two months so there hasn’t been as much time for new writing as I’d have liked! I have some ideas for new novels but it could be a while before they’re ready for their public debuts. I may share some fiction from my first novel, The Madonnas of Echo Park. I hope to read some new material by the end of my visiting year at GW.

Who are some of the writers of creative non-fiction you have been reading lately?

Likewise, book promotion doesn’t leave you enough time for reading but I have set aside space on the “to-read” shelf for Russians: The People Behind The Power by Gregory Feifer, Roxane Gay’sBad Feminist, Who Owns The Future by Jaron Lanier, and Orange is the New Black by Piper Kerman. You can see from this list that creative non-fiction is a large enough bookshelf to accommodate works of every topic and flavor. What I want as a reader is for a writer’s empathy to equal their knowledge, passion, or command of their subject. Empathy is the best tool in any writer’s arsenal – fiction or non-fiction – because it demonstrates you are an excellent listener. Empathy lets you observe the world and record your findings. That’s as good of a mission statement for “writer” as you’re going to get.