Paul Steinberg, JMM Seminar Alum, Publishes A Salamander’s Tale

|

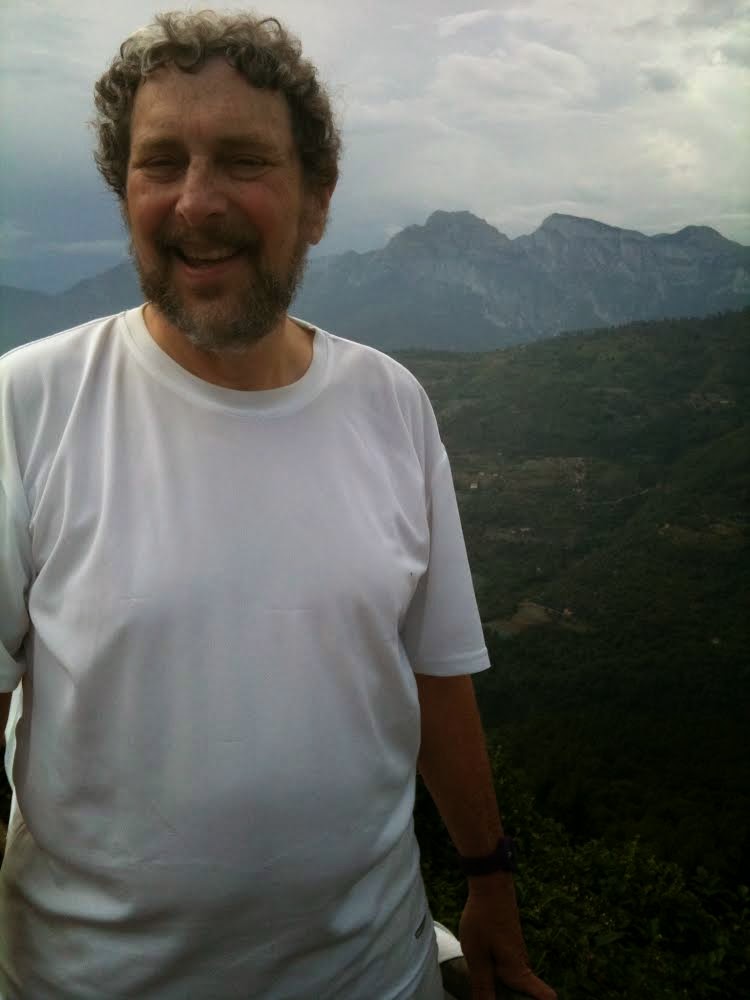

| Jenny McKean Moore seminar alum and author Paul Steinberg |

“A Salamander’s Tale is about Drugs, Sex, Lust, Rock ‘N Roll, Time, and Death”

Paul Steinberg, a longtime psychiatrist in Washington, graduated from GW’s Jenny McKean Moore seminar. His book, A Salamander’s Tale: Regeneration and Redemption in Facing Prostate Cancer, comes out next April. We talked to him about his time at GW, his work life, his relationship to literature, and his forthcoming book.

You were a student of Tilar Mazzeo by way of our department’s Jenny McKean Moore seminar, whose focus your semester was creative non-fiction. What was that experience like? Had you taken any literature/creative writing courses before this?

I found the creative non-fiction course extraordinarily helpful, especially in learning the “craft” of writing, also in figuring out timing, the most succinct way to put in a punch-line. I had never taken a creative writing course previously, although I had taken plenty of English courses in college. I had wanted to be an English major, but at the University of Pennsylvania in the late 1960’s, the rigidity of the English Department was striking. Although I had six years of Latin under my belt, the department chair insisted I had to take six semesters of a modern language. Fo’get about it! I ended up majoring in Political Science since it had the least demanding requirements; and it allowed me to take plenty of English courses and also complete the pre-med requirements.

You’re a psychiatrist here in Washington. In what ways did a career spent hearing other people’s stories prepare you for intensive reading in creative non-fiction? Were there particular writers you found especially useful, inspiring?

As I noted above, I wanted to learn the craft of writing, and the seminar provided all the stuff I was lacking. I had previously written a number of pieces in the Op-Ed section and the Science section of the New York Times, as well as pieces for the Washington Post, the Baltimore Sun, and the Los Angeles Times and elsewhere. But making non-fiction into something creative that reads like a novel was a skill I did not have. Kudos to Tilar Mazzeo for helping me with this skill.

As much as I love the salamander for its regenerative capacities, I love the fact that evolution has taken us from cold-blooded animals like the salamander to warm-blooded animals like ourselves – with the remarkable evolutionary development of the human brain. A salamander can survive for months while its tail or even part of its heart regenerates; but we human beings, warm-blooded, would have all sorts of bacteria growing in the wound site, and we would not survive.

So, we now have huge brains and enormous cognitive abilities – most of which we do not use as productively as we could. We lose something special in going from cold-blooded to warm blooded; but we gain something even more remarkable. The second half of the book, in fact, takes a look at how we can bust and debunk myths about sex and sexuality, about the gods, about time and death. It may be a bit pretentious, but I often tell friends that A Salamander’s Tale is about Drugs, Sex, Lust, Rock ‘N Roll, Time, and Death.

Advice for would-be writers: Again, everyone has a story. Something happens in everyone’s life. After all, none of us get out of here alive. We’re all busy living and busy dying. There’s a story in all of that, whether it’s presented in the form of fiction or non-fiction. Life is full of crazy events; and truth can be stranger than any fiction. Take advantage of the crazy bounces of life; and use them, instead of suppressing and dismissing them. Then learn the craft, and tell your stories in as entertaining and creative way as you can.